Graylingwell farm was officially closed in 1956 and farmlands were taken over by a tenant farmer and, on the 25th of March 1957, the stables were given to the hospital. In Graylingwell’s 61st annual report, the refurbishment of the farm buildings into a social centre was originally estimated to take five years but, with the enthusiasm of assisting patients on the job, this was likely shortened. In 1958, the stable yard had been re-concreted to form a games yard to complement the newly completed gymnasium fitted with changing rooms and shower and bathroom facilities and, by 1960, an industrial therapy room had been completed.

The late 1950s introduced to Graylingwell hospital the concept of occupational therapy (OT). It would be utilised to prevent and treat the inherent institutionalisation seen in long-stay patients and provide opportunities for all patients to gain confidence and capabilities in various work forces so as to support their lives after being discharged or during their visits to the day hospital. Each patient would be allotted tasks relevant and accessible to them, with long-stay patients focussing on utility and domestic projects as outcomes visible immediately to their environments was much more rewarding. Pre-existing OT centres set up tasks for male patients that would not ‘scorn’ their pride, including involvement with engineer staff, workshops and departments making toys and furniture, and working in the hospital gardens and grounds. In the 1958 annual report, overseers of OT, Miss M. Carter (Senior Assistant Matron) and Mr F. Murgatroyed (Senior Assistant Chief Male Nurse), reported 80-85% and 85% of their female and male patients respectively were occupied with tasks during the working week. It made significant improvements on the rate of deinstitutionalization, with 28 long-term patients being discharged from the hospital to gain full time employment by 1958 and five living at Graylingwell working at the proper job rate; only two patients needed to return to the hospital at the time. Two years later, the hospital had learned the strengths and weaknesses of its OT units, having published in the 1960 annual report that some female patients had no interest in sedentary tasks, thus further options were opened for them: crafts involving needlework, dressmaking, and laundry for themselves and other patients, large scale vegetable preparation in support of the hospital kitchen, domestic work and nursing support under supervision of staff, joining physical training groups, and some becoming involved with gardening. Men continued their work in the gardens, carpenters’ shops, and with painters, plumbers, and blacksmiths, as well as providing support work to the patient wards. Patients were involved in the ongoing project of converting the farm buildings into a rehabilitation unit, with completion of the gymnasium and industrial therapy rooms being included in the hospital’s 63rd annual report.

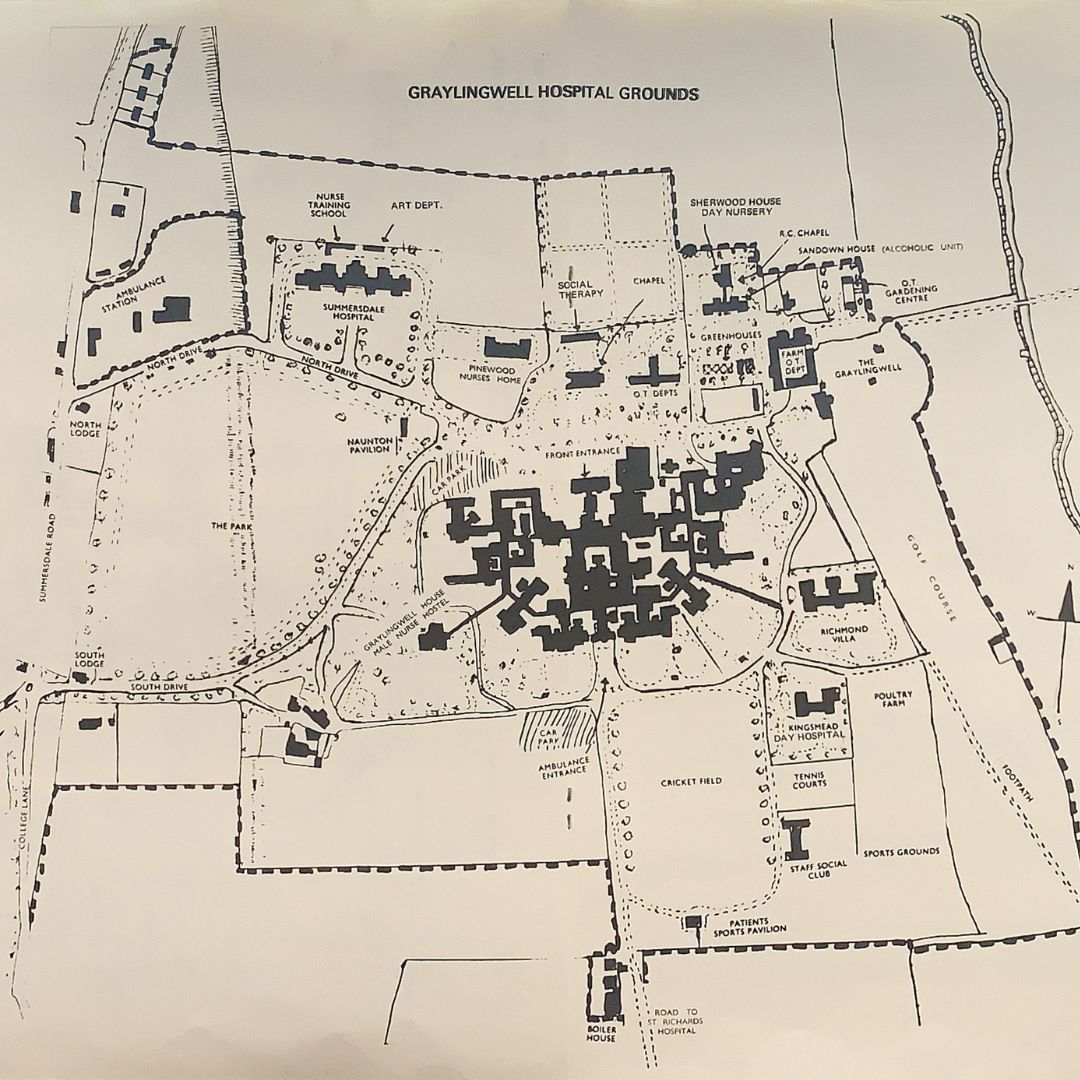

By the late 1960s, the Graylingwell Farm stables had been converted into rehabilitation units for various occupational therapies (Barone Hopper, Nurse and Social Worker at the hospital during the 60s and 70s, refers to this as ‘industrial therapy’), colloquially referred to as ‘sheds’, were numbered for each therapeutic focus they hosted. Patients would be escorted and monitored to various degrees by nursing staff, with five units available to accommodate their mixed needs and capabilities. Unit One hosted female occupational therapy (OT) patients focussed on more sedentary tasks like needlework (knitting and embroidery, for example), whilst Units Two and Three were for male patients committed to more the tedious work of disassembling wireless and telephone equipment into their separate components for use in factory reassembly. Male patients of more competent demeanours were set up in Unit Four where more creative tasks, like carpentry, were organised. Finally, Unit Five (known colloquially as The Barn) became the commercial space of occupational and industrial therapy. Both active and discharged patients worked together on an assembly line constructing DIY kits (such as hat stands and kitchen sink tray sets) to be collected by Hago Products in Bognor Regis. All patients clocked in and out each day, reminiscent of a genuine employed experience, and past patients were welcomed into the hospital OT space as a means of regaining their confidence in a setting familiar to them before continuing life outside of the institution.

Occupational therapy was a means of encouraging pride and fulfilment in patients as wages and evident work provided a sense of normalcy in a hospital setting. It also legitimised recreational therapy where patients would relax and enjoy various activities in the evenings and weekends; the 1958 annual report made mention of weekly cinema shows and television sets in each ward, socials held twice weekly, and sports including football, cricket, and netball for the female patients, as well as a yearly sports day which proved incredibly popular.

___

Research and text by Lily Richards, Chichester University